On the reissue of Not so Deep as the Well

I had seen these album covers somewhere before: one framed in yellow, the other in red, both featuring black and white photos of a dark-haired woman moving through landscapes of dirt and thistle. Or had I? They gave the impression of long familiarity, anyway. But the music was less intense, less brooding, than I had expected; I put it aside. It wasn’t until a year or so later when a friend sent me the debut album of the the French Canadian folk musician Myriam Gendron, Not so Deep as a Well, and I recognized the bright yellow border and the roving woman, that I began to find a feeling in the music to match the spectral cover photograph and discover the songs inside that have since become close companions. Songs of extremity, but also songs for daily life, “something to read in normal circumstances,” as Ezra Pound put it.

Actually, I have come to feel that Gendron (pronounced in French, “Jen-dron”) has produced two of the finest folk albums of the last decade. They are beautiful but unseasonable, belonging more properly to the penumbral years of the folk revival that produced outsider figures like Vashti Bunyan and Tia Blake. Maybe this is why from the start the albums have inspired outsized declarations of loyalty, professions of renewed belief in the cause of folk music from those who had lapsed into doubt and who perhaps wish they could still walk into a smoke-filled coffee house on MacDougal Street and find an anonymous Llewyn Davis playing there. Among this community of believers the albums have been passed hand to hand with some breathlessness. “I can say w/out caveat or fear of folly,” the rock critic Richard Meltzer wrote in the liner notes for her first album, “that the disc you now hold is the hottest—and FINEST!—Impossible Love collection in, I dunno, 30 years. 35! (True.) … ARE U READY 4 WOE?”

But newcomers to the church of Gendron may be surprised by what they find at the altar. Sonically, there is very little to hold onto: voice, acoustic guitar, light percussion, some field recorded noises scattered about. No Bob Dylan beatnik storytelling; no Joni Mitchell Canada, Oh Canada soaring to the skies. Nor, still, are the songs ostentatiously lo-fi. They are not the scratchings of naive genius. Quite clearly, they come out of an old faith in the structuring power of traditional song, each with its immemorial melody, its verses nailed together like the efficacious Shaker rocking chair – and out of a dream of the guitarist on a small spotlit stage strumming her tunes, the nightingale who sings for no one. “In a field / I am the absence / of field,” Mark Strand has written. It is the strength of an absence, I think, that is the first though not the last mystery of Myriam Gendron’s music. Everything that has been stripped away, texturally, instrumentally, has been stripped away so that we can better hear that absence.

Performing in Brooklyn last April, Gendron took to the stage in an all-black outfit, her hair worn just above shoulder-length and silvering. Alone with her guitar, Gendron cut a serious figure. She occasionally gave backstory to a song, but didn’t make jokes or court the crowd. Her hospitality was the music. For one tune she switched into a distorted electric guitar. “I used to be in a metal band,” she said. The audience laughed. “It’s true,” she said. The set finished with a rendition of what has become a signature cover, Michael Hurley’s “Werewolf Song.” It is a terrible and lovely song, about the loneliness of monsters, and it springs, like Gendron’s own music, from the dark side of folk.

Born in Ottawa in 1988, Myriam Gendron had the itinerant childhood of a diplomat’s daughter, spent in Washington, DC; Quebec; and Paris. Her musical education was thoroughly bilingual. On the Anglophone side: Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music; Dylan and the assorted Greenwich Village troubadours of the 60s; a lot of 90s grunge; the skeletal electrified blues of PJ Harvey and Cat Power. On the Francophone side: lullabies sung by her father; the dulcet-toned crooners of mid-century, Jacques Brel, Georges Brassens and Léo Ferré; and straddling the two languages, the looming presence of Leonard Cohen. Gendron arrived in Montreal at sixteen, where she was a book dealer for the last dozen or so years. She made a life there with her two children and partner, Benoît Chaput, who runs a small publishing house, L’Oie de Cravan (The Goose of Cravan), a very interesting project in its own right, apparently named after the poet-boxer Arthur Cravan.

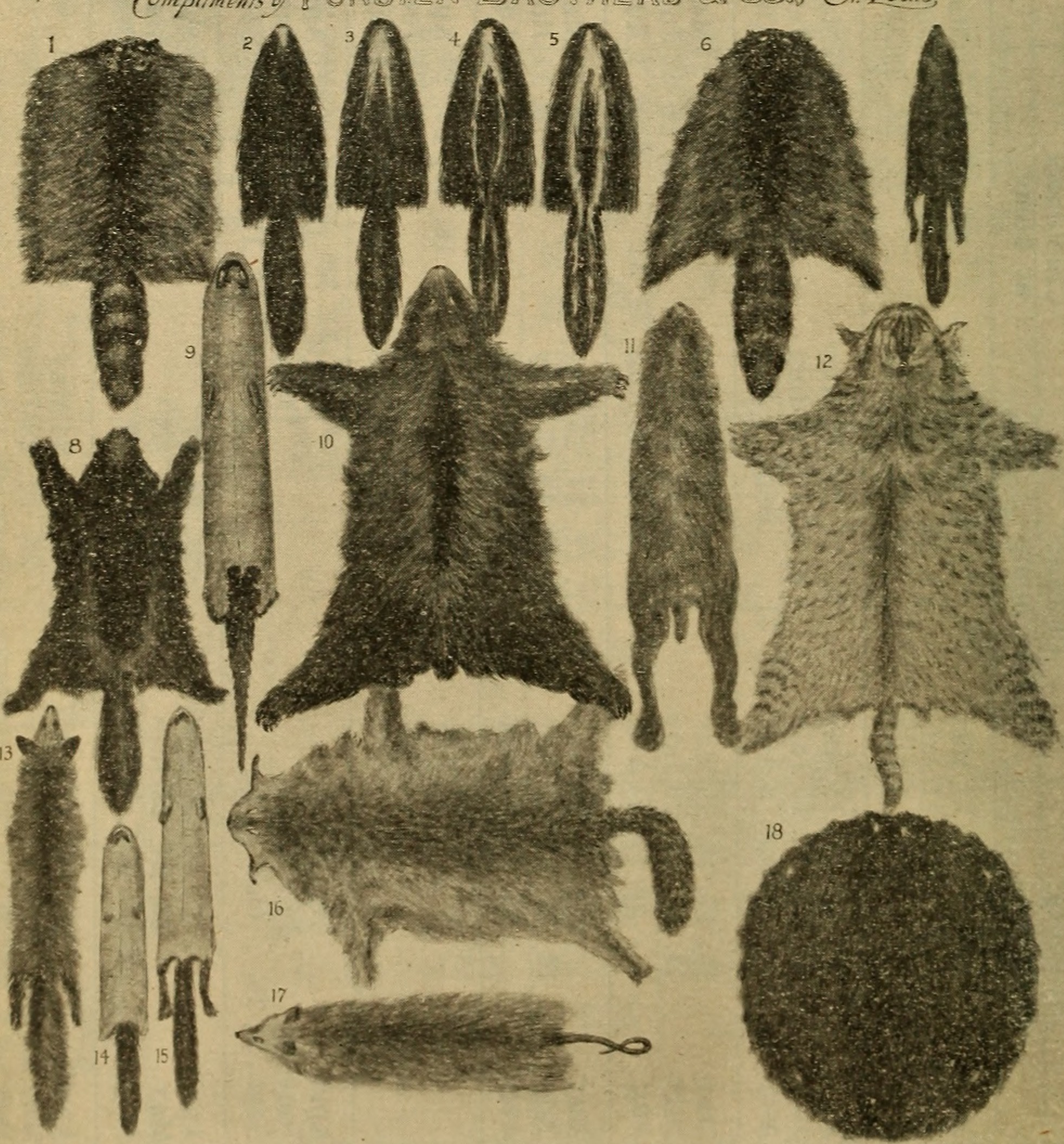

The story of Gendron’s first album is that of an artist who seems to stumble, or is urged, almost against her better judgment, into an encounter with the muse. After coming across a 1936 cloth edition of Dorothy Parker’s poems, Gendron began privately setting the verses to music. It was Chaput who encouraged her to perform the songs and get connected with a label. The resulting album, Not so Deep as a Well (2014) quickly found a set of converts. It was another seven years before her second album appeared, during which time she had two children and continued to work full time. For Ma delire – Songs of love, lost & found (2021), Gendron sleuthed deep in the annals of Quebecois traditional music. The record is a uniquely North American artifact; the French Canadian “Par un dimanche au soir” consorts amicably with John Jacob Niles’ Appalachian hymn “I Wonder As I Wander.” Occasionally national origins are lost to the fog of history, as with “Shenandoah,” which at one time was known as a triumphant Civil War classic, but which probably originates earlier, with canoe-going Canadian or American fur-trappers sailing the Missouri River.

One place to begin with the music is the unusual draw of Gendron’s voice. It is low, warm, smooth, and sits without reverb at the front of the mix in her albums. In recordings of unaccompanied solo voice, there is sometimes a quality of awkwardness, an almost eerie sensation that we the listeners are being addressed rather than simply tuning in or tuning out at our leisure. The victory of contemporary production technology has been to remove that awkwardness by making voices pure and liquid, and in doing so perfect the sovereignty of the listener over the recording. Gendron’s albums preserve something of the disarming feeling of address found in solo voice recordings, a feeling of being in the same room as the singer. Her primary language is French — she learned English at age ten — which may go some way in explaining the almost librarian-like pronunciation of her singing. Her “e” sounds stretch at length, and her “r”s and “l”s have a tendency to curl over and enclose words. A good vocal coach disciplines these linguistic tendencies out of students early on, guiding them toward open vowels, psalmic ahs and ohs. There has always been an irony in applying this standardizing method to folk singing, which thrives the closer it lives to vernacular forms of speech. Indeed, one of the revelatory aspects of Smith’s folk anthology was the way it unearthed for audiences reared on radio-friendly voices a bounty of American singing styles from the 1920s and 30s, some craggy, some shrill, some barely hewing to the shape of recognizable melody. Gendron’s voice is at home among these.

Not so Deep as a Well, happily reissued last month in expanded form, reveals Gendron not only as a singer of rare talent but a gifted arranger. What she has done is made the metropolitan wit of Dorothy Parker’s verse seem native to the slower-moving customs of folk music. To do this, Gendron has taken Parker’s brief lyrics, whose sing-song lilt can tilt into cloying rhyme, and given them new prosody. She has repeated certain lines where she’s seen fit. She has given the poems instrumental introductions and interludes, often lengthy ones, allowing the guitar to travel alone longer than one might expect. (It is stolid, beautiful, undexterous guitar-work. Its relatives are the various great fingerstylists, Michael Chapman, John Fahey, Glenn Jones, Jack Rose.) This may explain the assuredness — let’s not say asceticism — of the songs. They unspool with their own sense of time, nothing abbreviated.

And then there are the recurring figures that dance through the songs, drawn from the world of nursery rhymes and fairy tales. Princes and beggars, pirates and captives, magic red gowns, gallant men with hair like metal in the sun, bitter yellow berries. All of these glimpsed from the perspective of a child who has been slighted. She — the child narrator, Parker the writer, Gendron the surrogate — composes poems about her experiences (“Little things that no one needs,” she says), the themes of which are the connivance of age against youth and the dignity of sorrow against false consolation.

This is a young girl’s voice, then, or you might say, the voice of a child who has failed to become an adult, like one of Jean Rhys’ eternally innocent, eternally dejected vagrant women slumming it in Paris. Age does not make her wiser, it makes her sour. She has only her own truths to live on: she must reject the pseudo-comfort proffered by her pseudo-friends. Hence the ironically named “Solace:” “There was a bird, brought down to die; / They said, ‘A hundred fill the sky— / What reason to be sad?”’ And “The False Friends:” “And they were pitiful and mild / Who whispered to me then, / ‘The heart that breaks in April, child, / Will mend in May again.’” It is a poetry of irreconciliation and frustrated dreams, which savors the vinegary taste of disappointment on the tongue. The death of one bird, the wilting of even one flower is a tragedy to be mourned. This bitterness, finally, is a sustaining elixir. And so the denial of comfort that the songs practice is also a protest against the insensate moral life of grown-ups, whose maturity is numbness misnamed. Prickly, diminutive, righteous, Parker’s voice has become Gendron’s on Not so Deep as the Well, a collection of briars disguised as lilies.